Almere Utopian Fragments

Prix de Rome 2022: Healing Sites

The Netherlands has a long-standing history of bold, innovative, and large-scale spatial interventions. It is a country that has built itself from the sea up, inventing its own technologies and approaches along the way. Given its small geographical scale and its relatively large number of inhabitants, planning, logic, and structural organisation had be the base for any type of spatial development. This has led to a condition where almost the entire country feels (or is) constructed – there is barely any “real” nature to speak of, a territory which hasn’t been touched or created by a human hand. Observing from the air, the landscape presents itself as an overlay of various geometric grids, sporadically interrupted by islands of constructed green, blue or grey.

From a design perspective it could be perceived as a utopia, where anything and everything can be constructed. Architectural, urban, and infrastructural projects of all shapes and sizes find their way from imagination to reality, but often with increasing detriment to the already lacking natural environment. But in all the history of the Dutch built environment, there was, to date, no project more comprehensive, larger, and aggressive than the project of land reclamation. Although reclaimed areas of various sizes exist all throughout the country, the two most prominent projects (both in scale and recognisability) remain the creation of the Noordoostpolder and the Flevopolder, created during the Zuiderzee works in the 20th century. And while the Noordoostpolder generally remains in a sleepy, agricultural state as it was intended during its construction, the Flevopolder is still actively growing, developing, and densifying.

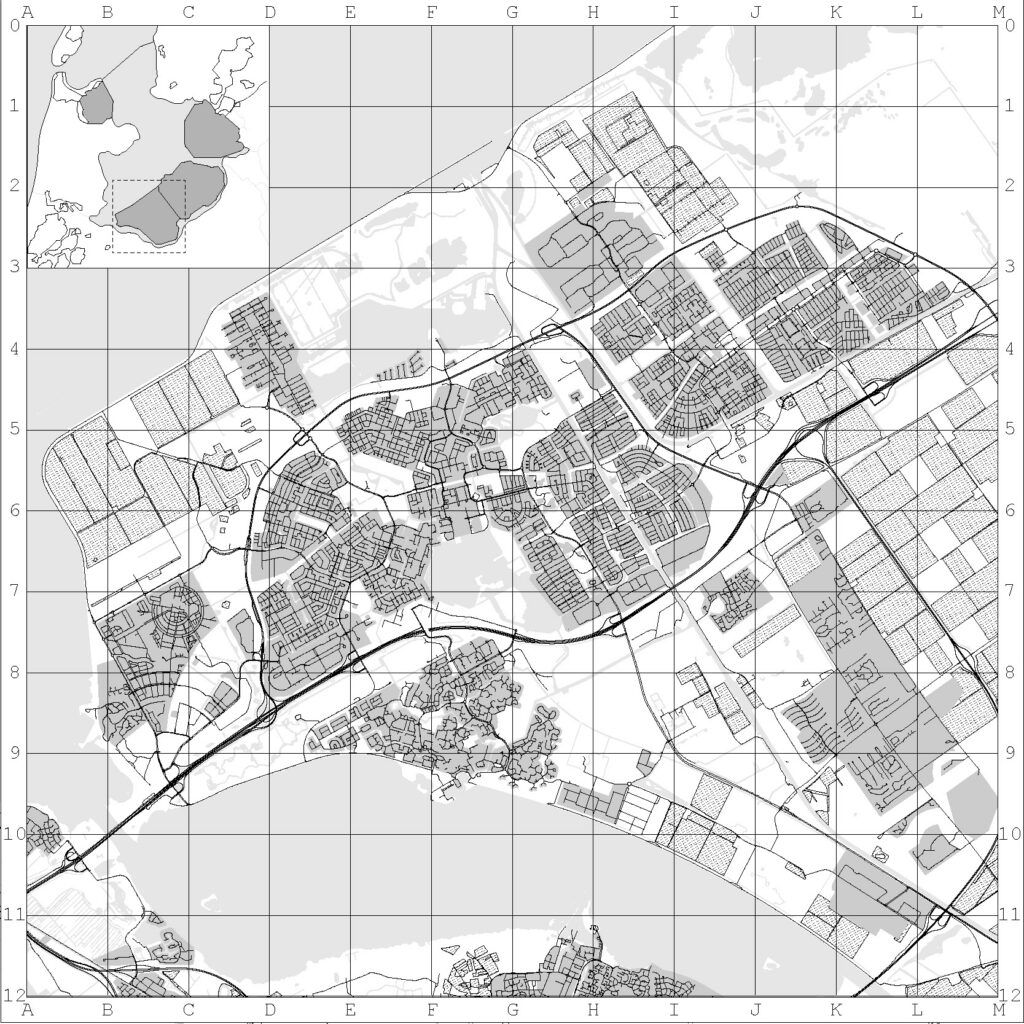

Seen as a site of the country’s biggest human-made injury to the natural environment, while consequently also being the location where many architectural dreams come true, the Flevopolder – or more precisely, it’s capital city of Almere – are chosen as the first Dutch Healing Site. Almere – the newest Dutch city, located on its youngest polder, has been rapidly developing since its construction in the 1970s, and is today seen as “the next big thing” – an exciting new urban area which is to take on (at least) the surplus of Amsterdam’s inhabitants. And while Almere was originally envisioned only as a cluster of villages providing suburban housing, similar in ethos to that of the Garden City model, today it is considered as the Netherlands’ fastest growing city. The developments which have occurred in this area since the seventies have caused the city’s spatial ambitions to change several times, each time accounting for an even bigger increase in population and popularity. The designs themselves have always been ambitious, to say the least. It can even be said that Almere is a site where most architectural and urban utopias have seen their physical manifestations: from the land reclamation project itself, creating almost a thousand square kilometres of land where once there was water; through the “picturesque” neighbourhoods each built with a specific theme in mind; various experimental competitions intended to test and develop new modes of living; to an ambitious masterplan for a city centre which was never really meant to be there; experiments in rule-less urbanism and architecture where the structure of an entire area is left to coincidence coming out of the imagination its users; all the way to an ambitious plan for the next decade which once again sees an expansion through the process of land reclamation (as if the already existing surface of the Flevopolder, currently covered mostly with agriculture, isn’t enough).

The Healing Site of Almere is approached through a fictional scientific analysis of its building blocks and history. It is seen as the site of multiple, layered utopian1 experiments – each with their own amount of success or failure, but also each indicative of the time in which they were constructed. If we view utopian projects not as whimsical and overzealous creation of an individual or group, but as an almost archaeological witness to a specific time and place in history, in which creative decisions were made as a response to specific social, political, scientific, or spatial conditions, we can use these utopian fragments to learn more about a space, and decipher its intricate logic and genesis. While utopian projects, when constructed literally and in their totality, often fail the test of time given the (usually) very specific demands that they strive to meet, the fragments which they are constructed of are often timeless and can be seen as current throughout the architectural and urban discourse. Seeing these projects not as only one overarching idea, but as a collection of spatial elements which came as a response to the needs of a specific time and place, we can begin to construct a collection of forms, tools, moves, and approaches which could be successfully revalidated and reused for future purposes.

The Healing Site of Almere is investigated through the format of a Medicine Box2 , which an examiner would carry along with them in order to assess the patient on site, perform analyses, and administer cures. In order for healing to begin, a correct anamnesis needs to be taken from the patient – what ailments have already transpired that have brought them to the condition that they are in today? Fragments of past utopias – seen as fictional or real events which occurred at a previous date – are collected, examined, and archived. Each found fragment is evaluated for the effects it had on the built environment – did it leave a scar, or antibodies? Is it seen as usable, or non-usable for future purposes? The locations on which the materials have been found (or the sites which they refer to), are carefully marked on an anatomically correct map of the site, in order to provide precise geographical location for any future examiners.

When all the evidence (or at least enough of it) has been gathered, the only question which remains is how to approach the healing process. Whether one should stick to modern methods where a cure is administered with the purpose of destroying the ailments and removing them from the body, or should more alternative approaches be considered: perhaps a homeopathic one in which more problematic fragments are reintroduced to the area, but through a small scale in order to become less invasive; or perhaps an acupunctural method in which specific nerves are struck in order to initiate the healing process? Regardless which method is chosen, it is imperative that it takes into consideration the multitude of built, imagined, failed, or successful utopian impulses found on the site. It is essential to work with them not through a formal approach which aims to copy what is already there, but through an analytical process which makes use of their methods rather than just their results. In this way, the utopian fragments scattered across the Healing Site of Almere, could possibly be revisited, re-evaluated, or reused in order to facilitate new approaches in this complex and important site.

1_ It is vital that the different projects which built up Almere be seen as utopian, instead of just being considered as speculative. While speculative designs often provide new forms and spatial approaches, utopian proposals have an added layer: that of the social. Each proposal which was developed for and around Almere should be seen as a utopian one since it had, as one of its main intentions, the ambition to change the way that people lived. While the results of these intentions are up for discussion, the ambitions they had, and the correlation of these ambitions to specific conditions of their spatial and historical contexts is undeniably utopian.

2_ The Medicine Box is created as a Black Box. The pun of this decision is not lost to the examiner: black boxes are notorious objects found at airplane crash sites which provide vital information on the events which preceded the accident – much in the same way as the Medicine Box provides a short material history of Almere.